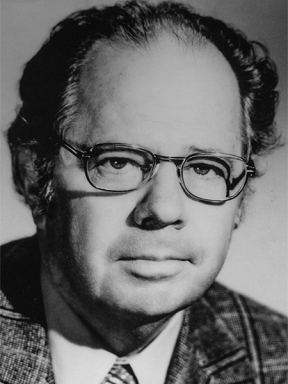

Hank Rieger was an American television executive and journalist.

Rieger helped to create and/or advance many of the television institutions that continue to thrive today, including the Television Academy, the Emmy Awards, ESPN (and the early days of cable TV), the Television Critics Tour and more. A visionary leader — first as a journalist and bureau chief for United Press, and later in public relations, including 15 years at NBC and nearly 40 years of association with the Television Academy, including serving as its president and founding publisher and longtime editor of emmy magazine — Rieger was defined by an extraordinary work ethic, a drive to succeed and integrity in all he did.

Never one to complain when work intruded, no matter the time of day, or distracted when working alongside Hollywood’s biggest stars, Rieger worked long past past the retirement age for most, serving clients’ public relations needs, notably ESPN. In 1994, the Television Academy honored Rieger with its Syd Cassyd Award, named for the Academy’s founder and given to select members in recognition of long and distinguished service. He was the third recipient of the award (Cassyd himself was the first), and to date it has been bestowed only eleven times in the Academy’s history.

"Hank Rieger worked tirelessly for many years on behalf of the Television Academy," said then-current Television Academy Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Bruce Rosenblum. "He believed in the Academy's ability to have a positive impact on the entire entertainment industry, and we are deeply grateful for all he contributed."

Henry Rieger, Jr. was born on September 20, 1918, in Kansas City, Missouri, to Henry and Ruth (St. Clair) Rieger of Phoenix (his birth took place while his parents were visiting family, and were advised not to continue traveling home to Arizona, which Rieger always considered his home, despite living in Missouri for his first six months). He was predeceased in 2013 by his wife of 65 years, Deborah A. (Hays) Rieger. They met in Phoenix, and his career led them to live in New York, Singapore, San Francisco, Pasadena and San Diego. He is survived by his sister, Ruth (John) Lepick of Long Beach, Calif.; his niece Julie (David) Burns of San Francisco; and his cousins JoAnn St. Claire of Westlake Village, Calif.; Ann Marie Carr of Tempe, Arizona; and Mary (Ted) Weeks, of Crystal Bay, Nev.

Childhood and College, First Exposure to Journalism

A child of the Depression who lost his father when he was 17, Rieger quickly learned the value of hard work. As a young boy, he was fascinated by the communications — at the time, newspaper — industry, thanks to tagging along with his sportswriter uncle, Darrell St. Clair, then of the Arizona Republic/Phoenix Gazette, to cover a golf tournament near Phoenix. Rieger went on to attend grammar school in Phoenix; high school in Riverside, Calif.; and to study English and journalism at Phoenix College and the University of Arizona (during which time he first worked for UP — later known as UPI). Later, he took courses at USC, where he eventually taught journalism and public relations for over two decades.

One thing about journalism he conveyed in his work and to his students, was the excitement of chasing a big scoop. “It’s an adrenaline thing,” he said in a 1999 interview. “It starts with you and goes with you the whole story.” Decades after his days at UP, and even after two lifetimes of success and travel and stories, Rieger still looked back most fondly at those early days as a reporter: “Those years at UP, those were the great years.”

He also cited this background as the perfect preparation for the second half of his career, on “the other side,” in public relations. He believed ex-newspaper people “make the best” public relations people. “They know the news business and they know what makes the news and they know what doesn’t make the news…(and) most news people who are in publicity are good writers, and you need good writing.”

All that said, his respect for the press remained, and he knew the limitations of trying to lead them to the story you want them to write. “You don’t control the press,” he said. “You might try to direct them and lead them, but you sure as hell are not going to control them.”

From the Military to UP

Before his career could take off, Rieger was drafted as World War II was getting underway overseas, and was sent to Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas. He was assigned to a horse cavalry, but as the only one among his group who could type, he was made the company clerk. He later served at Williams Air Force base near Phoenix, and in Miami, where he — and fellow draftee Clark Gable — was trained for flying. He was also assigned to intelligence and counter-intelligence training. Later roles took him to the Philippines, Honolulu and Australia. After a series of promotions, he rose from the rank of Private and left the military as a Major.

In a sense, his career in public relations began during his military service, as he handled press relations for his base. In early 1946, while finishing his tour of duty in San Francisco, he began unpaid work for UP, leading to a paid position on the night shift. He soon was transferred to Phoenix as bureau manager. The hours were long — as a wire service, they were constantly on deadline — and the pay was low ($16 per week to start), but in 1999, Rieger said, “I miss those 2 o’clock in the morning phone calls. I really do!”

Hank and Debbie married on October 5, 1947, and in 1951 he was transferred to the UP office in Los Angeles, as the day manager. While there, he was exposed for the first time to two things that would soon define his life’s work — the entertainment industry and television.

The primary “beat” for his UP office was the growing entertainment industry, including extensive coverage of the Academy Awards. The Emmy Awards, by comparison, were not even staffed. Their prominence would arise years later, under Rieger’s leadership.

A Year in Singapore, Back to UP…Breaking the Marilyn Monroe Story

In 1953, Rieger took a one-year leave of absence and served the State Department in Singapore as a press attaché for the consul general. True to his lifelong affection for work and staying busy, he called the job “boring…all you had to do was go to the top ten reception every night with the consul general.” It is not surprising to learn that Rieger spent much of his free time that year helping out at the local UP office.

After Singapore, Rieger and his wife returned to San Francisco, only to move in 1956 to Los Angeles, when he was placed in charge of the UP bureau there, as well as San Diego and Las Vegas. It was there that Rieger broke the biggest story of his journalistic career — and took much delight that he beat his longtime competitor, AP, on the breaking news: the death of Marilyn Monroe. An unofficial UP reporter — a tipster, paid per tip provided — called the Rieger home at 1 a.m. and simply said, “Hank, Marilyn Monroe is dead. Check Beverly Hills police.” Quickly, Rieger verified the death with the police, dictated the news flash to his one staffer in the office, called colleagues with assignments to various places of interest around town and went into the office to work the phones.

From Los Angeles, UP sent Rieger to New York, as news editor. There, a call out of the blue changed the rest of his career. The Southern California Gas Company was seeking a news manager — public relations. At first, Rieger couldn’t envision the 180-degree change: “I’m one of those guys who would die being a news man,” he said. But sufficient wining and dining — along with his wife Debbie’s preference for the West Coast — brought Rieger back to L.A. on “the other side of the fence.”

A New Career in PR, Rubbing Elbows with the Stars

In 1965, after only two years with SCGC, Rieger was hired by NBC as director of press and publicity. During 15 years at the network, he led publicity efforts for such landmark television programs as Bonanza (NBC’s first show in color), I Spy, Julia, The Monkees, Star Trek, Laugh In, and Sanford and Son. He also directed publicity efforts for the 1972 move of The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson from New York to Los Angeles.

Despite his initial reservations, Rieger thrived in his new profession. He discovered that the battle with the other networks — for the most elaborate PR campaigns, press exposure, exclusive interviews and magazine covers — fed his competitive spirit, just as racing AP for a scoop had done. His journalistic instincts also came to bear in dealing with tragic news, including the 1977 suicide of Freddie Prinze, the 22-year-old star of NBC’s Chico and the Man.

During this time, Rieger worked alongside many of the biggest executives in television (including David and Tom Sarnoff, Julian Goodman, Bob Kintner, Grant Tinker, Herb Schlosser and Brandon Tartikoff), as well as the biggest stars — Carson, Dean Martin, Redd Foxx, Bob Hope, Danny Thomas, James Garner, Angie Dickinson, and Sammy Davis Jr.

Some of Rieger’s most memorable adventures came when travelling with Hope. In December 1969, at the White House, Hope performed for President Richard Nixon. Following the accompanying state dinner, Rieger asked Nixon for an autograph — much to the chagrin of the Secret Service. Never one to be star struck, Rieger only joined the line after it had formed... with the full cast of Hope’s “Gold Diggers” dancers.

The next morning, it was Rieger who talked Hope into going on a trip to entertain troops overseas. Hope was suffering from eye problems, and wanted to cancel. But after an hour with Rieger, weighing the pros and cons, the trip was on, and Rieger accompanied the legendary performer for two weeks of up to four performances per day at military bases in Berlin, Istanbul and Bangkok. It was at the latter that even Hope’s star was out-shined, when he was joined by Neil Armstrong, who a few months earlier had become the first man to walk on the moon.

Rieger was even called in to help answer the NBC phones on November 17, 1968 — the so-called “Heidi Game.” In the Eastern half of the country, an NFL game between the Oakland Raiders and the New York Jets was cut off late in the action to begin the movie Heidi, as scheduled at 7 p.m. The network’s switchboard was flooded, and for more than an hour Rieger apologized to caller after caller, vowing it would never happen again.

Another unexpected role came during a strike of writers and reporters at NBC News — for two weeks, Rieger was pressed into duty as an on-air correspondent and host of a weekend political talk show. One exclusive story came through a source who knew then-Governor Ronald Reagan often got his hair cut at Paramount Studios, where Rieger interviewed the future president.

On to the Academy, Leaving a Legacy

Rieger’s work at NBC included frequent involvement with the Television Academy and its Emmy Awards. Over the years, and with Rieger’s urging, the Emmy Awards — from the nomination announcement to the presentation and other events throughout the year, plus the launch of emmy magazine, which Rieger founded — grew in stature among Hollywood’s elite and the entertainment press. He also was intimately involved with the dispute — and ultimate 1977 split — between the organization’s New York and Los Angeles chapters. The result was the East Coast-based National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences with rights to the Daytime, Documentary, News and Sports Emmy Awards, and the West Coast-based Academy of Television Arts & Sciences, which retained rights to the Primetime Emmy Awards.

Rieger became the first president elected after the formation of the new Television Academy, a two-year stint, but his years of service to the Academy left an enduring impact. Two of the many achievements for which he was most proud were the Student Awards and the growth of the internship program. As a PR professional, he also was always quick to cite the growth in media coverage of the Emmy Awards. In addition, as the founding publisher of emmy magazine, he set the editorial direction and created a publication that served its members, the industry and interested television viewers and continues to do so today.

On to the Olympics, and ESPN

In the fall of 1979, Rieger was again recruited to new employment — as director of public relations for the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, working for Peter Ueberroth. At NBC, Rieger had had some Olympic involvement, and saw the L.A. Games as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. It was a move he would ultimately regret. Less than a year later, he handed Ueberroth his resignation.

At that point in his career, Rieger wanted to be his own boss as a public relations consultant. Within weeks, another old contact from NBC, Chet Simmons, who had run the sports division, called Rieger, having heard he was seeking clients. In 1979, Simmons had surprised the sports-media world by leaving NBC to lead a fledgling, ill-funded organization with the far-fetched idea of a 24-hour-a-day cable television sports network. It was ESPN.

Although Rieger had many clients, his relationship with ESPN and its communications department was special to both sides, and continued to his final days. Through his reputation and relationships, Rieger lent instant credibility to ESPN among the media. His sage counsel, boundless willingness to provide assistance at West Coast events — from the Television Critics Association meetings in Los Angeles to the various America’s Cup events in San Diego — and encouragement were invaluable, leaving a lasting impression on all with whom he worked.

Along the way, he was also brought back into the fold at emmy magazine, out of need, as editor. Although it was intended as a stopgap position, Rieger served in the role until 1994. His desire to keep busy in later years also included lending his guidance to San Diego State University’s film department and, of course, walking his and Debbie’s various dogs over the years, including their Champion Soft-Coated Wheaten Terrier.

Rieger died March 5, 2014, in Oceanside, California. He was 95.