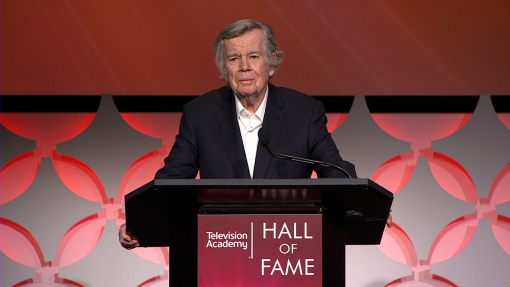

“The overwhelming and surprising reception of Dragnet was the greatest compliment ever paid to me as an individual, and is sufficient for the rest of my life,” the late Jack Webb once said of the series that he created, starred in, produced, directed and frequently wrote.

Webb was a struggling film actor only a few seasons before Dragnet premiered on NBC Television in January 1952. But he soon became one of early television’s most prolific producers after his portrayal of Los Angeles Police Department Sgt. Joe Friday routinely pursuing “just the facts” became a national icon.

Among the series produced by Webb's Mark VII Productions Ltd. were the landmark reality-inspired programs Adam-12, The D.A., Emergency, True, Hec Ramsey, Mobile One, and Project UFO. Webb also produced and starred in several feature films, including Dragnet. In 1963, he served as executive in charge of television production at Warner Bros.

Throughout his career, Webb advocated accuracy in his dramatizations. “Although Dragnet was entertaining, or it wouldn't have lasted as long as it has,” Webb observed, “it was a documentary — documentary in nature and flavor. There were a few police shows [before Dragnet], but ours was the first to use actual cases and the documentary technique.”

Universal-MCA president Sidney Sheinberg, who worked with Webb when Dragnet was reprised for four years starting in 1967, credits him with pathfinding the trail for contemporary reality-based programs.

“If Jack is not the father of reality programs, he is one of the major ancestors," Sheinberg says. “That goes not only for the cop shows, but also, in a sense, to all of the reality shows. This is because Jack re-created stories in a fashion that was intended to simulate reality in a very specific way: Jack Webb’s perception of reality. His shows were characterized by a very simple style of storytelling, directing and acting. He wanted to make them real in every sense of the word.”

Sheinberg also praises Webb’s straightforward approach to filmmaking. “One of the most interesting things about Jack is the simplicity with which he approached his subject,” Sheinberg observes. “He really made a virtue out of simplicity to the point where ‘just the facts’ became nearly a joke. But that was his attitude about the whole process of filmmaking and, in an odd kind of way, life. He was a slightly unusual character in that he was a strong and loyal friend in a business where strong and loyal friends are not necessarily the rule. And Jack had a great sense of responsibility that was quite significant, whether it was toward the people he went into business with, governmental agencies or the people who were financing him.”

Born in Santa Monica in 1920, Webb was raised only a few blocks from downtown L.A.'s City Hall by his mother and grandmother after his father abandoned them when he was one year old. To support his elderly family during the depths of the Depression, Webb declined an art scholarship at the University of Southern California to work as a men’s clothing salesman.

“My mother and grandmother worked when they could,” Webb recalled, “but most of the time we were on relief. I remember the sacks labeled BEANS and the sacks labeled RICE and the day-old bread the county gave out."

During World War II, the six-foot, 165-pound Webb served in the Army Air Corps and emceed two USO troop shows. After receiving a hardship discharge in early 1945, he began his career as a radio announcer in San Francisco and became the private detective of the title in the radio serial Pat Novak for Hire.

After three years in radio, Webb returned to Los Angeles, where he appeared in his first feature film, Hollow Triumph. (His latter features included Sunset Boulevard, The Men, The D.I., and, reflecting his lifelong interest in jazz, Pete Kelly’s Blues.)

In 1949, Webb appeared as a crime-lab detective in He Walked By Night, a film noir that realistically depicts an LAPD dragnet. Working with two local police detectives who served as technical advisers on that film gave Webb the idea of dramatizing actual police stories.

“There weren’t many takers,” Webb wrote in 1961 of the radio executives who turned down his proposed police-detective series in 1949. “It wasn’t simply that Dragnet was a new idea that made it hard to sell. It was the idea of cops being normal, plain guys working for a paycheck that seemed to pose a mental block for most program executives. It seemed that where there were cops, there had to be robbers. And where there were cops and robbers, there had to be violence. Almost nobody could see the value in the facts that policemen don’t always shoot-’em-up or get into brawls with thugs and hoodlums.”

Dragnet became the number-one show on radio in 1950, and Webb nixed any format changes for television. “What television didn’t understand, and apparently hasn’t yet,” Webb continued in 1961, “is that violence can be effective just by suggestion or innuendo. We often went for months without anyone on the show getting so much as a blister.”

Bert Fields, Webb's attorney and close friend, says, “Jack was a visionary. The first glimmerings of shows like Hill Street Blues can be seen in Dragnet’s workmanlike attitude. Instead of a shoot-'em-up, cops-and-robbers show, Jack was way ahead of his time with a much more realistic and complex show. His idea was to turn the camera on a couple of cops as they go about their lives. It was plodding when other shows were doing melodramatic stories. There was nothing melodramatic about Dragnet.”

Dragnet ran for seven years in the 1950s. When Dragnet was reprised in 1967, Webb hoped that it would be “like revisiting an old friend.”

Married four times, Webb became so closely identified with Friday that he claimed to be “amused” by viewers who thought that he was Friday.

“Friday is actually a neutral character,” Webb said. “He has no religion. He’s had no childhood, no educational background, no war record. No personal side at all.”

Dragnet's law-and-order message was close to Webb’s heart, but he avoided politics. “It’s not up to me to be politically involved,” Webb said. “It's not a question of rightist or leftist. The underlying theme is: Crime doesn’t pay. We take no sides.”

Nevertheless, during the turmoil of the 1960s, Webb said that he hoped “that a series like Dragnet can do something to help restore respect for the law. I don’t want to palm myself off as a do-gooder. After all, I’ve been divorced.”

Harry Morgan, who played Friday’s LAPD partner in the ‘60s series, recalls Webb’s efficiency as a director and producer.

“We did many episodes in two days,” Morgan says, “some of them in one day, which is pretty remarkable. And even when we were shooting for two days, they were not long days. We worked to maybe 4:30 and then we went up to Jack’s office to have a few belts, which he liked to do. Jack knew every second what he wanted and how to do it. It was a static show, in that there wasn’t a lot of running around, but it didn’t require anything else. The stories were all honest and actual cases, and the way he chose to shoot them was very successful.”

More personally, Morgan remembers Webb as “a gregarious, congenial associate. Jack had kind of a dour expression and laconic speech and did not appear to be a terribly affectionate man on Dragnet. In reality, he was just the opposite. He was a man of great warmth, generosity and affection.”

Webb died suddenly during the early morning hours of December 23,1982. The LAPD remembered him in the only memorial service it has ever conducted for a “civilian,” and then permanently retired Badge 714.

This tribute originally appeared in the Television Academy Hall of Fame program celebrating Jack Webb's induction in 1993.