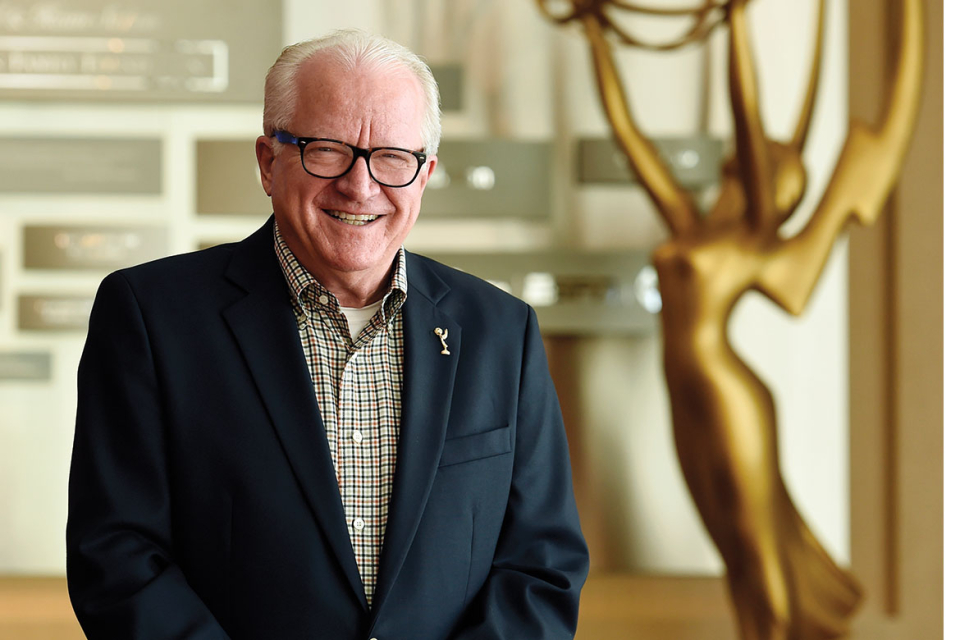

When he published his dissertation on screenwriter and author Irving Wallace back in 1974, John Leverence was of course well acquainted with Wallace's best-seller The Prize, about the annual awarding of the Nobel Prize.

With his PhD from the Center of Popular Culture at Bowling Green University, Leverence was then headed toward a career in academia.

But Wallace's The Prize — which was made into a movie starring Paul Newman — may have sparked Leverence's interest in his ultimate professional path as an awards executive. In 1980 he joined the Television Academy, where he stayed for some 40 years, overseeing the Emmy Awards competition and becoming among the foremost authorities in the awards and recognition field with his 1998 book, And The Winner Is ....

When Leverence came aboard, the Hollywood-based Academy — then known as the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences — was emerging from a fraught era, having split from the New York–based National Television Academy in the late 1970s (the so-called "divorce" brought the Primetime Emmys to the West Coast, and left the Daytime, News and Sports Emmys in the East).

Leverence's influence was profound during this time, and his professorial air and genial nature provided steady leadership across the decades. In December 2019 he retired as senior vice-president of the awards department, remaining to serve as chair of the Engineering Emmy awards committee for the 2020 season.

During his tenure, the Academy witnessed momentous changes in television as the medium evolved from broadcast-only to cable, then streaming. From the large-scale issue of how to define television to the nitty-gritty of managing the Emmy calendar, Leverence brought his keen intellect and good humor.

In 2010, he was honored with the Academy's Syd Cassyd Founder's Award, which recognizes members — and in Leverence's unique case, an Academy staffer — who have made a significant, positive impact on the organization over many years of involvement and service.

Leverence was interviewed in October 2019 by Jenni Matz , director of The Interviews: An Oral History of Television, a program of the Television Academy Foundation. The following is an edited excerpt of their conversation. The entire interview can be screened at TelevisionAcademy.com/Interviews.

Q: What prompted you to pursue a master's degree and then a PhD?

A: I enjoyed academic life and wanted the career security of a tenured position. While in graduate school at the University of Chicago, I heard that Ray Browne, the father of academic popular culture studies, had recently initiated a PhD program at Bowling Green University's Center for the Study of Popular Culture. With Ray as my dissertation advisor, it was an ideal fit.

I got a job in the radio-television department at Cal State Long Beach, where I greatly enjoyed teaching for a few years. Then I moved from what turned out to be a faux academic situation to my true one at the Television Academy, where my 40-year stint proved to be the tenured academic career I had hoped for.

I started in January 1980, shortly after the split with the National Academy [NATAS]. The [Hollywood-based] Academy was very much a brand-new, somewhat iffy thing. Our Academy [ATAS] didn't have a lot of money and operated with a barebones staff.

We had our wonderful executive director [Tricia Robin], a bookkeeper, somebody who took care of membership, another who did student programs, three of us in awards, and that was about it. We were a very small nonprofit association operating with a certain degree of uncertainty, if you will, about just exactly how and, at times, if the enterprise was going to proceed and succeed.

Q: Because of the split with NATAS?

A: The split with NATAS was traumatic. There was terrible bitterness between the two academies. And it was a situation in which we were trying to establish our identity and move forward.

The new Academy was based on a single premise: if you're going to be giving an important award like the Emmy, you need to give it peer to peer. The structure of the National Academy was chapter-based, with various chapter cities and regions around the country that included us, the Hollywood Chapter.

It was in Los Angeles where national, primetime entertainment programming was being made. And there was one group in particular — art directors and production designers — who felt that it was inappropriate that somebody who operated a camera at a station in Boston was to be voting on art direction and production design for a primetime Hollywood production.

Chapter-based versus peer-based Emmy judging was the defining philosophical difference between NATAS and Hollywood that, in the bitter end, could only be settled by a "divorce" lawsuit.

Q: As television evolved over the years, were you part of discussions about how to define the medium?

A: The discussions we'd have — "Should we be the Television Academy or the Telecommunications Academy?" — it was like Saint Thomas Aquinas trying to figure out how many angels could dance on the head of a pin.

The talks would go on and on into the night at board meetings and sub-committee meetings. Ultimately we reasoned, "Well, it's a big tent — everybody's in. Let's not get too picky about exactly what we're calling ourselves." Everybody knows what we are: we're the Television Academy.

Q: Would you walk us through the nomination process for the Primetime Emmys?

A: Well, everything backs up from the date of the telecast, which has almost always been in mid-September.

The annual review of Emmy rules and procedures begins right after the telecast, when the awards committee convenes to review two kinds of requests: one is housekeeping —which is just what it sounds like, minor adjustments — and the other is substantive changes that have to do with changes in eligibility — that could be a new awards category, or perhaps adding a couple different job titles into eligibility.

Those substantive requests — and the housekeeping requests that come out of the awards committee meetings in the fall — go forward to the Academy's board of governors for consideration in the early part of the new year.

Once our rules and procedures are set, we start our entry period, which leads to the nomination stage. The entries are checked and rechecked, then listed on ballots — by performer, writer, et cetera — again, the peer ballots. The only non-peer situation is programs — comedy series, for example, is judged by everybody, whereas director in a comedy series is judged only by directors.

We send the ballots digitally to all voting members of the Academy. They cast their votes, again digitally. The top vote-getters in each category — five, six or seven, depending on the designation — emerge as the nominees.

After that first round of nominations voting is complete, we go on to the second phase, which determines the winners. The results are tallied and then are locked in the aluminum briefcases that our accountants display during the show — these cases are handcuffed onto their wrists! And, of course, we announce the winners on our show in mid-September.

Q: Does anyone at the Academy know the results in advance?

A: All the counting is exclusive to the accountants. For example, if I'm sitting at my computer and voting, my vote travels directly to the Los Angeles headquarters of Ernst & Young. That's where it ends. It doesn't go to the Academy. It doesn't go to anybody else.

Q: How has the evolution to multi-platform programming affected the Emmy telecast?

A: Mass-market programming — broadcast- network shows like NCIS — still get the biggest audiences, as opposed to many of the streaming shows, like The Handmaid's Tale , Fleabag, Russian Doll.

These niche shows are often very high in quality, but low in terms of widespread viewing by the general public. So, as seen at the 2019 Emmys, you had an extraordinary line-up of nominees and winners, but you had a 30 percent drop in tune-in. It's a situation in which you have a diminished audience because you have a diminished distribution of the programming that you are recognizing.

In 1980, the first year I was at the Academy, I think we had an audience of about 46 million viewers for the telecast. Moreover, back in those days there was a "gentlemen's agreement" among the networks that on Emmy night — because the show was on a wheel [alternating by year among ABC, NBC, CBS and Fox] — there was not going to be highly competitive programming.

When NBC introduced Sunday Night Football in 2006, the death knell tolled for traditional Emmy ratings.

Q: Has there ever been talk of moving the Emmys from Sunday to, say, Saturday?

A: There has been. But historically the lowest ratings of the week are on Saturday. That's an absolute dead zone.

Q: And why September and not earlier in the year, when the other entertainment award shows are airing?

A: When all of this was set up back in the 1940s, the broadcast networks concluded their primetime season with May sweeps. Then you would have summer reruns. Remember summer reruns? If you'd missed a show, you could watch it over the summer when it was going to be on again.

Then when basic cable came along, savvy execs like Barry Diller said, "We see a hole here: the broadcast networks effectively go to the beach during the summer." All of a sudden, we were getting hot and heavy programming12 months out of the year.

The Emmys were originally meant to air on the Sunday night before the beginning of the fall season. If your network had the show that night — if the show were on, say, CBS — instead of selling your commercial time, you would keep it for yourself to promote your shows. The Emmys were an opportunity to look back on the prior year, recognize the best programming and also promote what was coming for the fall.

Q: Does that annual calendaring still work?

A: I think that it's irrelevant now. If you watched the [2019] Emmys, you saw a lot of promotions for upcoming programs, but had the show been in March, there still would have been a lot of promos. It's no longer a situation in which things shut down for the summer months, then pick up again in September.

Q: Are there any Emmy rules changes you've personally championed over the years?

A: I was very keen to move the Engineering Awards out of the Creative Arts and into its own stand-alone show, which it has had for many years now.

The Engineering Awards are the fifth and final awards show that we have in the course of the year, and it's my favorite. I really like working with the Engineering Awards committee, and I like how they're identifying and recognizing cutting-edge technology. That committee is to the Academy as All Souls is to Oxbridge.

Also, there did not used to be an award for casting, and I helped draft the argument for that. I argued that an Emmy was completely legitimate because casting was but a seamless component of the casting-performance continuum.

Stunts was another of the crafts that did not have an Emmy. We don't consider stunt eligibility to be tied to how deftly you can jump off a bridge; rather, we consider how well the leap was choreographed. The award is for stunt coordination, which is a subgroup of choreography. Once we established that there was a paradigm in choreography for Emmy eligibility, we could establish a paradigm for an Emmy in stunt coordination.

Q: What about the Emmy statue itself? How did it evolve?

A: It was originally designed in 1948 by Louis McManus, a television production designer. There was a competition, and he submitted a painting of his wife as Brunhilde, the Wagnerian Valkyrie with feathery wings and a horned helmet. We went from that to another version in which we got rid of the feathers and reconfigured them as lightning bolts.

Along with the atom — or electron, as some people have identified it — you've now got references to TV as an electronic medium. But you also have this character — the muse of art, if you will — and she is uplifting, exalting the electron of science atop a Mercator grid of the world.

That's the symbolic meaning of this beautiful art nouveau statue known as the Emmy Award. It was originally dubbed an "Immy," referencing a low-light picture tube called the image orthicon tube. But Immy was ultimately feminized to Emmy.

What other secular organization in this town has as its trademark icon a statue of a goddess? It's a little bit strange if you think about it... a little bit pagan. But she is as symbolically represented by it as she is numinously present within it. That's the essential thing about her.

While I love the bold deco design of the Oscar statuette that makes it the epitome of a masculine, patriarchal award, the Emmy is of a feminine, matriarchal cast, wholly imbued with a proper goddess's deathless substance and living nuance.

Q: Even after the Emmy is awarded, the Academy retains ownership of the statuette, correct?

A: Right. You can keep it in your family, will it to a relative or return it to the Academy.

Q: What kind of reactions have you seen when people win an Emmy?

A: I have spent many an Emmy Sunday evening watching people come off stage with their Emmys. We used to hand them a prop Emmy on stage. When they'd exit, I would be there saying, "Great job. May I have this? We will be sending you your 'real' Emmy at a later time." [Now winners receive their real Emmy on stage and may have it inscribed with their name at the Governors Ball.]

I remember one winner, at the Creative Arts, who said to me, "Oh my God, no. I am going right now to the hospital to be with my dying mother. She said, 'Honey, if you win the Emmy, please come right over and let me see it.'" I told him, "Oh, please, here's the Emmy... go!" But generally when people come off stage, they're in a daze — like they don't know where they are or what they just said. They are really in a stupor.

Q: As an academician, how do you assess the Academy's archival efforts?

A: As you know, [television executive] Dean Valentine, who'd been inspired by the Shoah Visual History Foundation, came before the board of governors many years ago and said, "You need to set up an archive. You need to do videotaped interviews [with TV professionals for historical purposes]." Exactly what we're doing here today. I remember that meeting very well.

With that, we established the Academy as a place of very significant academic research. This [oral history collection, The Interviews: An Oral History of Television] is an astonishing resource. And thanks to Dean's prescience and good timing, it got started [in 1996] when you could still reach back into the earliest days of television and talk to the pioneers.

What if we were here some 20-plus years later without having invested much time and treasure in The Interviews? I think we would be guilty of letting slip one of our most lasting and significant contributions to the culture of television.

Q: What have you enjoyed most about administering the Emmys?

A: The lovely people I have been blessed to work with and the distinguished Academy I have been privileged to serve.

For the complete interview, please click HERE

This article originally appeared in emmy magazine, Issue No. 1, 2021